The Surfaces Below

Landscape is traditionally understood to be horizontal, something that extends laterally in space. In historical landscape paintings artists used perspective to create the illusion of distance, of depth. The “horizon line” marks the place where land and sky meet at the limit of our vision. But in many ways, rock is vertical not horizontal. It towers above us, it extends below our feet, and it blocks our ability to see past it into the fictional depth of landscape painting. Stene’s paintings ask: What would it take to come to terms with the verticality of the mountain? How could we make sense of a landscape that doesn’t have a fixed horizon line? How would a landscape look if we tried to view it from below?

In the 1700s mines extended deeper into the earth than ever before. Miners climbed up the face of the mountain to the pithead. There, they entered tunnels through which they travelled hundreds of meters downward. Perhaps it was mining that made the landscape into something fundamentally vertical. Or, perhaps it has always been vertical and mining simply allowed humans to re-orient themselves, to acknowledge the verticality of rock.

John Smith, Junction of Mona and Parys Mountain Copper Mines, 1790. Watercolour and pencil on paper. Artwork in the public domain. Image credit: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales.

In this watercolor of a Welsh copper mine from 1790, enormous caverns have been carved into the mountain. Cast in deep blue and green shadow, the subterranean void created by copper mining is just as impenetrable as the rocky face of the mountain. Even though it is empty space, it has its own kind of mass and density. You cannot see past it. You cannot optically experience it as depth. The way is blocked.

As you navigate the landscapes created within Stene’s exhibition, you are immersed in a space structured by surface rather than depth. The canvases rotate in their frames; they can be rearranged and explored. You can chart your own path around them. But the terms of the encounter are determined by the rock, not the viewer.

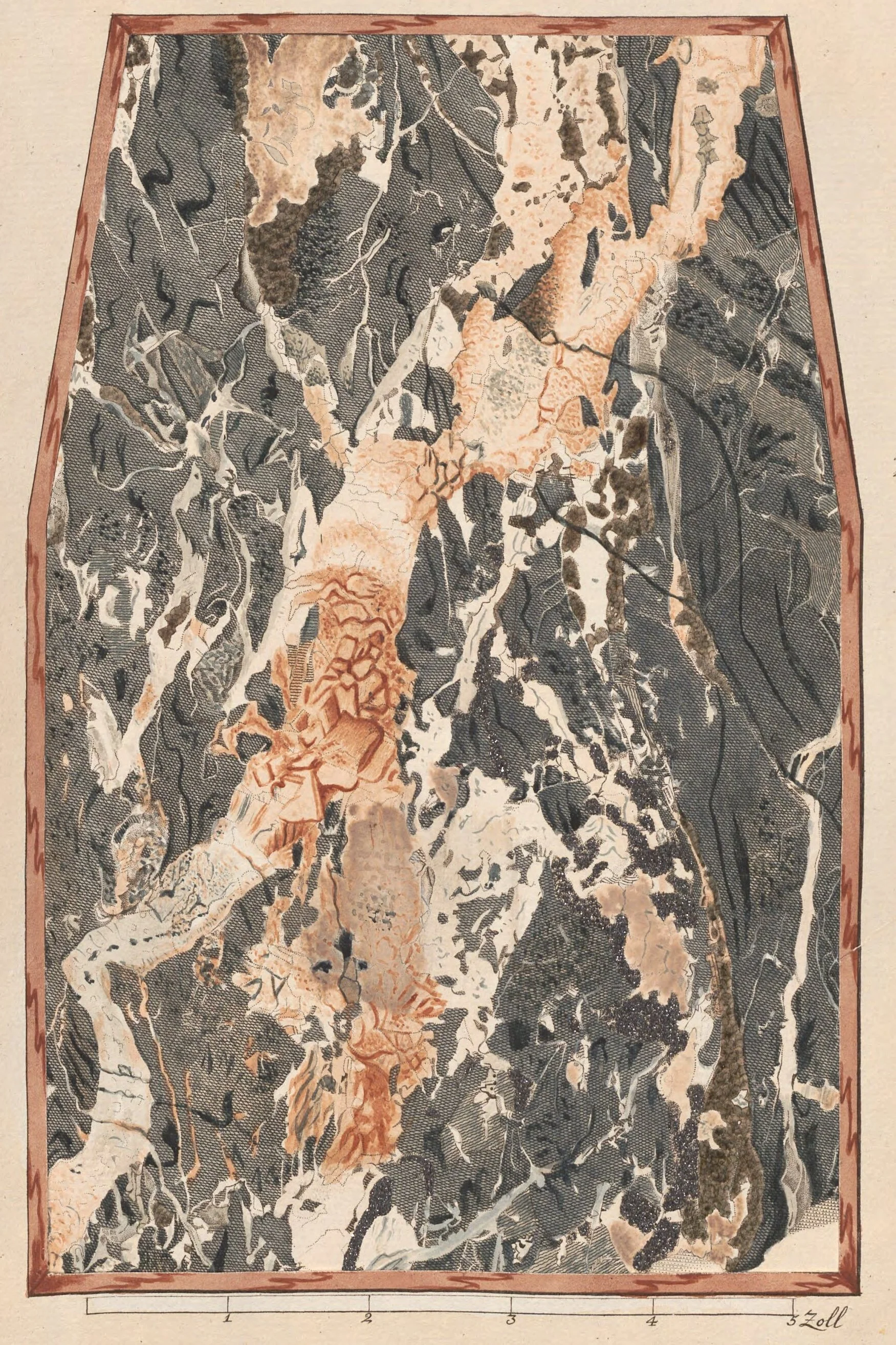

F. H. Spörer, Plate II in Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich von Trebra, Erfahrungen vom Innern der Gebirge (1785). Artwork in the public domain. Image credit: Patrick Anthony.

In 1785, this mining diagram was published in Saxony. The brown wooden frame seen around the ore in the diagram represents an adit, the entrance of a mine typically supported by timber beams.

The large wooden frames surrounding Stene’s paintings are also adits, in a sense. They serve as an entrance to a space you cannot actually “enter”: instead, the viewer comes face to face with the brightly textured, unyielding materiality of the mountain. But Stene shows that this materiality is not static or mute. It vibrates with its own layered internal intensities. It is forever forming and reforming itself.

Dr Stephanie O’Rourke

Senior Lecturer in Art History, University of St Andrews